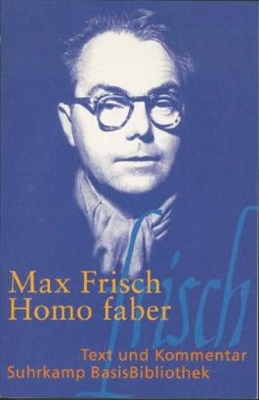

The novel is a note by Harry Galler, found in the room where he lived, and published by the nephew of the mistress of the house in which he rented a room. On behalf of the mistress’s nephew, the foreword to these notes was also written. It describes Galler's lifestyle, gives his psychological portrait. He lived very quietly and closedly, looked like a stranger among people, wild and at the same time timid, in a word, seemed like a creature from another world and called himself the Steppe wolf, lost in the wilds of civilization and philistinism. At first, the storyteller is wary of him, even hostile, because in Galley he feels a very unusual person who is very different from everyone else. Over time, alertness is replaced by sympathy, based on great sympathy for this suffering person, who failed to reveal all the wealth of his powers in a world where everything is based on the suppression of the will of the individual.

Galler is a scribe by nature, far from practical interests. He does not work anywhere, lies in bed, often gets up almost at noon and spends time among books. The vast majority of them are the writings of writers of all times and peoples from Goethe to Dostoevsky. Sometimes he paints with watercolors, but always one way or another dwells in his own world, not wanting to have anything to do with the surrounding philistines, who successfully survived the First World War. Like Galler himself, the narrator also calls him the Steppe Wolf, wandered "into the cities, in the herd life" - no other image will more accurately draw this person, his timid loneliness, his savagery, his anxiety, his homesickness and his homelessness. " The hero feels in himself two natures - the man and the wolf, but unlike other people who pacified the beast in themselves and accustomed to obey, "the man and the wolf did not get along in it and did not help each other for a long time, but were always in mortal hostility, and one only plagued the other, and when two sworn enemies converge in one soul and one blood, life is worthless. ”

Harry Galler tries to find a common language with people, but crashes, even communicating with his own kind of intellectuals, who turn out to be the same as everyone, respectable inhabitants. Having met a professor in the street and visiting him, he cannot stand the spirit of intellectual philistinism, which pervades the whole atmosphere, starting with a sleek portrait of Goethe, "capable of decorating any bourgeois house", and ending with the loyal arguments of the owner about the Kaiser. A furious hero wanders around the city at night and realizes that this episode was for him “farewell to the philistine, moral, learned world, and was filled with the victory of the steppe wolf” in his mind. He wants to leave this world, but is afraid of death. He accidentally wanders into the Black Eagle restaurant, where he meets a girl named Germina. They start a kind of romance, although it is rather a kinship of two lonely souls. Germina, as a more practical person, helps Harry adapt to life by introducing him to night cafes and restaurants, to jazz and his friends. All this helps the hero to more clearly understand his dependence on the "philistine, lying nature": he stands for reason and humanity, protests against the brutality of the war, but during the war he did not allow himself to be shot, but managed to adapt to the situation, he found a compromise, he is the enemy power and exploitation, however, in the bank he has many shares of industrial enterprises, on the interest of which he lives without a twinge of conscience.

Reflecting on the role of classical music, Haller sees in his reverential attitude towards her “the fate of all German intelligentsia”: instead of knowing life, the German intellectual obeys “the hegemony of music”, dreams of a language without words, “capable of expressing the inexpressible”, eager to go into a world of wondrous and blissful sounds and moods that "never turn into reality", and as a result - "the German mind missed the majority of its original tasks ... intelligent people, all completely did not know reality, were alien to her and hostile, and therefore "in our German reality, in our history, in our politics, in our public opinion, the role of intelligence was so miserable." Reality is determined by generals and industrialists, who regard intellectuals as "an unnecessary, divorced from reality, irresponsible company of witty talkers." In these reflections of the hero and the author, apparently, lies the answer to many “damned” questions of German reality and, in particular, to the question of why one of the most cultured nations in the world unleashed two world wars that almost destroyed humanity.

At the end of the novel, the hero finds himself in a masquerade ball, where he plunges into the elements of eroticism and jazz. In search of Hermina, dressed as a young man and defeating women with “lesbian magic”, Harry finds himself in the basement of the restaurant - “hell”, where devil musicians play. The atmosphere of the masquerade reminds the hero of Walpurgis the night in Goethe's Faust (masks of devils, wizards, the time of day is midnight) and Hoffmann's fairy tales visions, which are already perceived as a parody of the Hoffmann, where good and evil, sin and virtue are indistinguishable: “... a hoppy dance the mask gradually became a kind of crazy, fantastic paradise, one after another the petals seduced me with their aroma <...> snakes seductively looked at me from the green shade of foliage, a lotus flower soared over a black quagmire, firebirds on branches lured me ... " The hero of the German romantic tradition fleeing from the world demonstrates a split or multiplication of personality: in him a philosopher and dreamer, a music lover gets along with a killer. This happens in the "magic theater" ("entrance only for the crazy"), where Haller gets with the help of a friend of Hermina's saxophonist Pablo, a connoisseur of narcotic herbs. Fiction and reality merge. Haller kills Hermina - either a harlot or her own muse, meets the great Mozart, who reveals the meaning of life to him - she should not be taken too seriously: “You must live and you must learn to laugh ... you must learn to listen to the damned radio music of life ... and laugh at her fuss. ” Humor is necessary in this world - it must restrain from despair, help maintain reason and faith in a person. Then Mozart turns into Pablo, and he convinces the hero that life is identical to the game, the rules of which must be strictly observed. The hero is comforted by the fact that someday he can play again.